- Home

- Robert Mason

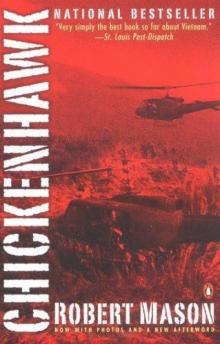

Chickenhawk

Chickenhawk Read online

Chickenhawk

Robert Mason

More than half a million copies of Chickenhawk have been sold since it was first published in 1983. Now with a new afterword by the author and photographs taken by him during the conflict, this straight-from-the-shoulder account tells the electrifying truth about the helicopter war in Vietnam. This is Robert Mason’s astounding personal story of men at war. A veteran of more than one thousand combat missions, Mason gives staggering descriptions that cut to the heart of the combat experience: the fear and belligerence, the quiet insights and raging madness, the lasting friendships and sudden death—the extreme emotions of a “chickenhawk” in constant danger.

Robert Mason enlisted in the army in 1964 and flew more than 1,000 helicopter combat missions before being discharged in 1968.

[Chickenhawk]’s vertical plunge into the thickets of madness will stun readers.

(Time)

Mason’s gripping memoir… proves again that reality is more interesting, and often more terrifying, than fiction.

(Los Angeles Times)

Very simply the best book so far out of Vietnam.

(St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

Robert Mason

CHICKENHAWK

For Patience and Jack

Author’s Note

This is a personal narrative of what I saw in Vietnam and how it affected me. The events all happened; the chronology and geography are correct to the best of my knowledge. The names of the characters, other than the names that are famous, and unimportant characteristics of all the persons in the book have been changed so that they bear no resemblance to any of the actual people in order to preserve their privacy and anonymity.

I’d like to put in an apology to the grunts, if they resent that term, because I have nothing but respect for them and the conditions under which they served.

I hope that these recollections of my experiences will encourage other veterans to talk. I think it is impossible to know too much about the Vietnam era and its effects on individuals and society.

Instead of dwelling on the political aspects of the war, I have concentrated on the actual condition of being a helicopter pilot in Vietnam in 1965—66. The events, I hope, will speak for themselves.

I want to thank Martin Cruz Smith, Knox Burger, Gerald Howard, Constance Cincotti, Jack and Betty Mason, Gerald Towler, Bruce and Susan Doyle, and Jim and Eileen Helms for their generous aid and encouragement.

I am particularly indebted to my wife, Patience, for her unflagging support in difficult times, both in the writing of the book and in the life that it’s about.

Map

Bell HU-1 Iroquois Schematics

1. Heating Burner and Blower Unit

2. Engine

3. Oil Tank Filler

4. Fuel Tank Filler

5. Transmission

6. Hydraulic Reservoir (Pressure Type)

7. Forward Navigation Lights (4)

8. Pilot’s Station

9. Forward Cabin Ventilator (2)

10. Cargo Suspension Mirror

10A. Pitot Tube (Nose Mount)

11. Tail Rotor (90°) Gear Box

12. Aft Navigation Light

13. Tail Rotor Intermediate (45°) Gear Box

14. Synchronized Elevator

15. Tail Rotor Drive Shaft

16. Anti-Collision Light

17. Oil Cooler

18. External Power Receptacle

19. Cargo-Passenger Door

20. Passenger Seats Installed

21. Swashplate Assembly

22. Landing Light

23. Copilot’s Station

24. Search Light

25. Battery

26. Alternate Battery Location (Armor Protection Kit)

27. Pitot Tube (Roof Mount)

28. Aft Cabin Ventilators (2)

29. Stabilizer Bar

29A. Hydraulic Reservoir (Gravity-feed type)

30. Engine Cowling

Cockpit

1. Pilot’s Entrance Door

2. Sliding Window Panel

3. Hand Hold

4. Shoulder Harness

5. Seat Belt

6. Shoulder Harness Lock-Unlock Control

7. Collective Pitch Control Lever

8. Seat Adjustment Fore and Aft

9. Collective Pitch Down Lock

10. Seat Adjustment Vertical

11. Directional Control Pedal Adjuster

12. Microphone Foot Switch

13. External Cargo Mechanical Release

14. Directional Control Pedals

15. Cyclic Control Friction Adjuster

16. Cyclic Control Stick

17. Microphone Trigger Switch

18. Hoist Switch

19. Force Trim Switch

20. Armament Fire Control Switch

21. External Cargo Electrical Release Switch

22. Search Light ON-OFF Stow Switch

23. Landing Light ON-OFF Switch

24. Landing Light EXTEND-RETRACT Switch

25. Search Light EXTEND-RETRACT LEFT-RIGHT Control Switch

26. Engine Idle Release Switch

27. Collective Pitch Control Friction Adjuster

28. Power Control (Throttle)

29. Power Control Friction Adjuster

30. Governor RPM INCREASE-DECREASE Switch

31. Starter Ignition Trigger Switch

Prologue

I joined the army in 1964 to be a helicopter pilot. I knew at the time that I could theoretically be sent to a war, but I was ignorant enough to trust it would be a national emergency if I did go.

I knew nothing of Vietnam or its history. I did not know that the French had taken Vietnam, after twenty years of trying, in 1887. I did not know that our country had once supported Ho Chi Minh against the Japanese during the Second World War. I did not know that after the war the country that thought it was finally free of colonialism was handed back to the French by occupying British forces with the consent of the Americans. I did not know that Ho Chi Minh then began fighting to drive the French out again, an effort that lasted from 1946 until the fall of the French at Dien Bien Phu, in 1954. I did not know that free elections scheduled by the Geneva Conference for 1956 were blocked because it was known that Ho Chi Minh would win. I did not know that our government backed an oppressive and corrupt leader, Ngo Dinh Diem, and later participated in his overthrow and his death, in 1963.

I did not know any of these facts. But the people who decided to have the war did.

I did know that I wanted to fly. And there was nothing I wanted to fly more than helicopters.

I. VIRGINS

1. Wings

The experimental division authorized to try out [the air assault] concept is stirring up the biggest inter-service controversy in years. There are some doubts about how practical such a helicopter-borne force would be in a real war.

—U.S. News & World Report. April 20, 1964

June 1964—July 1965

As a child I had dreams of levitation. In these dreams I could float off the ground only when no one watched. The ability would leave me just when someone looked.

I was a farm kid. My father had operated his own and other farms, and a market, in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and West Virginia. When I was nine he started a large poultry farm west of Delray Beach, Florida. Here, in between chores, I daydreamed about flying to the extent that I actually built tall towers to get off the ground.

By the time I started high school my father had switched from farming to real estate, and we moved to town. In my junior year a friend, a fledgling pilot, taught me the basics of handling a small plane. The airplane was a vast improvement over my dreamy mechanisms. It worked every time. By the time I graduated, I had a private pilot’s licens

e.

In 1962, after two years of sketchy attendance at the University of Florida, I dropped out to travel around the country.

A year later, in Philadelphia, two very important things happened to me. I met Patience, my wife-to-be, and I applied to be a pilot candidate in the army.

I thought I had finally achieved my goal of-goals when I arrived at the U.S. Army Primary Helicopter School at Fort Wolters, Texas, in June 1964. I drove through the main gate. Helicopters flitted over the nearby mesas; helicopters crisscrossed overhead; helicopters swarmed everywhere. My companion, Ray Ward, craned his head out the window and grinned. He had also joined the army to fly helicopters.

We drove up to a group of concrete buildings that looked like dormitories. A sign out front said WARRANT OFFICER CANDIDATES REPORT HERE. We were impressed. Having gone through basic training at Fort Dix and a month of advanced infantry training at Fort Polk, we thought that all buildings in the army were World War II vintage, wooden and green. I stopped the car.

“Hey, this is nice.” Ray smiled. “Ask that guy where we should put our baggage.”

The guy he was referring to was walking quietly toward us, a sergeant wearing a white helmet and bright armbands. But we were no longer trainees and had no need to be afraid.

“Say, Sergeant,” I asked amiably, “where should we put our luggage?”

“Luggage?” He flinched at the civilian word. Neither Ray nor I had on uniforms.

“Uh, yeah. We have to check in before five, and we need a place to change into our uniforms.”

“You’re candidates?” he asked calmly, quietly, with the ill-hidden contempt I had witnessed so many times before in basic training.

“Uh-huh.” I nodded, bracing myself.

“What the fuck are you doing driving around here in civvies? You think you’re tourists?”

“No—”

“You get that car over there in that lot. Now! You will carry your luggage back here, double time! Now, git!”

“Yes, Sergeant,” I said automatically. As I backed away, the sergeant watched, glaring, fists on hips.

“Turn the car around,” said Ray.

“Not enough time.” I backed all the way to the parking lot.

“Oh, shit,” said Ray. “This is not gonna be a picnic.”

Neither of us had suspected that the army taught people how to fly helicopters the same way they taught them to march and shoot. But they did.

The 120 candidates in our class were known as WOCs—for “warrant-officer candidates.” A warrant officer is appointed, not commissioned, and specializes in a particular skill. There are electronic-technician warrants, supply warrants, and warrant-officer pilots, among many other specialties. The warrant ranks—WO-1, CW-2, CW-3, and CW-4—correspond to second lieutenant, first lieutenant, captain, and major, and warrant officers receive the same privileges and nearly the same pay as commissioned officers.

When I first heard of the warrant-officer-aviator program, I was a civilian and cared little what the rank meant. All I knew was that they flew.

The flight program was nine months long. It began with one month of preflight training and four months of primary flight training at Fort Wolters, followed by four more months of advanced flight training at Fort Rucker, Alabama. Preflight training was a harassment period designed to weed out candidates who lacked leadership potential. If you made it through that initiation, you got to the flight line and actually began to learn to fly. Then they tried to wash you out for mistakes or slowness in flight training, on top of the regular hassles in the warrant officer program.

Preflighters ran wherever they went, sat on the front edge of their chairs at the mess hall, and had to spit-shine the floors and keep precisely arranged clothing in their closets. We were allowed to leave the base only for two hours on Sunday, to go to church. It was the same kind of bullshit I had gone through in basic training, except worse.

The TAC sergeants assigned us to various slots in a student company: squad leaders, platoon leaders, first sergeant, platoon sergeants, and so on. One of us would be the student company commander. We would hold these positions for a week while the instructors tried to drive us crazy and graded our reactions. Unfortunately I was assigned to be the first student company commander.

Some seasoned army veterans had volunteered to be flight candidates. Others, like Ray and me, were just out of basic. To be fair, God should have put one of the experienced guys in the company-commander slot. But God, personified in the form of TAC Sergeant Wayne Malone, was seldom fair.

My first official act as the student CO was to get the company to the mess hall, four blocks away. Pretty simple stuff. Attention. Left face. Forward, march. Stop. Eat.

But Sergeant Malone, his fellows, and the senior classmen created obstacles. They stood directly in front of me, yelling in my face, while I tried to tell the company to come to attention.

“Well, candidate. Are you going to the mess hall or not?” screamed a senior classman whose nose almost touched mine.

“Yes, sir. If you’d get out of my way, I‘ll—”

“What?” Shock and disbelief. “Get out of your way!” Immediately my antagonist was joined by others.

“Candidate, you can’t talk to your superiors like that!”… “Get this mob to the mess hall before they close the place!”

“Yes, sir!” I could barely hear my own voice. “Company, attention!” I yelled. No one heard me over the screaming TAC sergeants and seniors.

“They can’t hear you,” yelled a senior, his breath blasting into my face.

I tried again. Still, no one could hear. I raised my arm straight up and back down and heard a student platoon leader yell, “Attention!” Command hand signals?

As soon as my classmates came to attention, some seniors leapt among the ranks, yelling,. “Did you hear him call attention, candidate? Then why did you come to attention, candidate? There are no arm signals for attention, candidate!” And so on. Eventually, because the mess hall would close, they allowed my commands to get through.

Then it was double time to the mess hall, and chin-ups and push-ups outside. Inside, we sat on the edge of our chairs and ate with our forks rising vertically from the plate and making a right angle to the mouth. Harassment is common to all officer-candidate schools, but what did it have to do with flying? The answer is that everybody in the army is a soldier first, his specialty second. It was going to be a long nine months.

During that first week, I had to get us to classes on time, see that our rooms were perfect, and God forbid anyone had a dirty belt buckle. I never broke down and cried during the hazing, as some did, but my reaction was still unsatisfactory. I returned the glaring screams of the hazers with glaring screams of my own. Resistance plus obvious inexperience got me a poor grade for my turn at command. Sergeant Malone, who kept a plaque in his office inscribed Woccus Eliminatus, would often whisper in my ear while I stood in formation, “You’ll never make it, candidate.” And when the four weeks of preflight ended, Malone had indeed put me on the list of twenty-eight candidates who would go before the elimination board.

I remember feeling sick in a dim hallway the night before I was to see the board. I had failed before I had even gotten a chance to sit in a helicopter. If they washed me out of flight school, I would have to serve my remaining three years of enlistment as an infantryman. The embarrassment was intolerable. Ray Ward and I had come through basic and advanced infantry training to get to flight school, and I had failed in the first month. Ray had encouraged me before the list was posted, telling me that I had really done well, that they weren’t going to eliminate me. I remembered Malone’s whispered threats. Also, a TAC officer announced that I was definitely not pilot material, based on his analysis of my handwriting. I knew I’d be on that list. I was.

Patience and I had decided that she and our one-month-old son, Jack, would live with my parents in Florida until I had made it past preflight. Then they would come out to Texas and live near t

he base. I almost called to tell her I had blown it. I couldn’t. I decided to wait until after the elimination board.

The next day, the board called in the twenty-eight doomed candidates one by one. By the time my name was called, after lunch, I was numb. I remember walking into the board room tingling with fear and energy. I sat on the edge of a chair in the middle of the room. A major looked at me for a few moments and then at the report in front of him. Seven other members of the board watched me closely. A stenographer’s fingers moved at a machine when the major spoke.

“It says here that you failed to show any sort of enthusiasm in the leadership drills. Your instructors say you weren’t interested in participating seriously when you were selected to be the student company commander.”

And then I talked. I can’t remember exactly what I said, but I said it calmly and rationally, opposite from the way I felt. I told them I was just out of basic and inexperienced. I was very serious about getting through this school, but I might not have shown it. I had been flying since I was seventeen. “I want to be a helicopter pilot,” I said. “I’ve studied for that, and I think my grades from ground school prove it. When I’m out there someday flying soldiers around, I expect to be one of the best pilots that ever came out of this school. Won’t you give me that chance?” I went on for five minutes.

The stenographer nodded that the words were down. The major made a mark in my folder. “Wait in the company area until you hear from us.”

I waited with packed duffel bags, watching my classmates avoid me and the other washouts. When a runner from the office called my name, I jumped out of my skin. I burst through the door at the student company headquarters, came to attention, and screamed, “Candidate Mason reporting as ordered, Sergeant!”

Malone only looked at my feet and screamed, “You missed the white line, candidate! Go out and try again.”

Chickenhawk

Chickenhawk