- Home

- Robert Mason

Chickenhawk Page 2

Chickenhawk Read online

Page 2

I about-faced, went outside, and tried again to hit the painted white line in front of Malone’s desk with just the tips of my boots, without looking down. After two more attempts, I succeeded. Malone swaggered menacingly up to me, coming in from the side. My eyes were glued to the wall in front of me. Malone talked into my ear.

“It pains me to tell you, candidate, that the elimination board, in its infinite wisdom, has decided to reinstate your ass.”

I turned, grinning at the news.

“Eyes front, candidate!” My head snapped to the front. “Yes, they have decided to reinstate you, over my violent objections, I might add. So get your lucky ass out of here and go join your classmates. Git!”

I turned and ran out the door, laughing all the way back to the barracks. I called Patience and told her to come.

The next morning, I was called back to the office. The board’s decision to reinstate me had ruined the student-instructor ratio at the flight line. Malone grinned. “So, Candidate Mason, you will be starting preflight all over again with the next class. Maybe this time I’ll see you eliminated.”

The second time through preflight was much easier. I had already taken all the classes, so I scored terrific grades on every test. I had learned to play the leadership game with great zeal. I became the almost perfect preflight candidate, but Malone said, “You’ve had plenty of practice, Candidate Mason.”

Two months after I had driven through the main gates, I finally got to the flight line. We were issued flight suits, flight helmets, flight gloves, sunglasses, Jeppson course plotters, wind-face computers, and new textbooks. We were told to wear our hats backward on the flight line, the traditional mark of the unsoloed pilot candidate. We still ran everywhere else, but we were driven to the flight line. We were starting the real business of this school.

We marched into a low building adjacent to the main heliport and sat at gray tables, four candidates to a table. The flight leader gave us a brief talk and then the IPs (instructor pilots) came into the room. IPs were mythical beings whom we held in the highest respect. They were civilians. We had heard a hundred stories about their training methods, their short tempers, and how they liked to get rid of students so they would have a lighter load. They strode through the door wearing the same gray flight suits we wore, a kind of mechanic’s coverall with a crotch-to-neck zipper and a dozen pockets all over it. The IPs had something sticking out of each pocket. We knew they were privileged by how sloppy they were.

The IP who came to our table would take the four of us on our orientation flight, the only “free ride” in the course. We had been preparing for this day by studying helicopter controls and basic flight maneuvers. Many of us felt we could fly in an hour or so.

I had spent many evenings in my room reviewing the flight controls, what they did, and how I would have to move my hands and feet. I could hear the ground school’s aerodynamics instructor in my head. “The names of the controls in a helicopter refer to their effect on the rotating wings and the tail rotor,” the voice would say. “The disk formed by the rotor blades is what really flies. The rest of the fuselage simply follows along suspended from the disk by the mast.” In my chair I formed a strong mental image of this disk spinning over my head. Then I would start to review the controls. “The collective control stick is located on the left side of the pilot’s seat. Pulling it up increases the pitch angle of both main rotor blades at the same time, collectively, causing the disk, and the helicopter, to rise. Lowering the collective reduces the pitch, and the disk descends. The throttle twist grip on the end of the collective stick has to be coordinated with the up and down movements. You must twist in more throttle as you raise the collective, and roll it off as you lower it.” I raised and lowered my left hand by my side, twisting it from side to side as I did.

“The cyclic control stick rises vertically from the cockpit floor between the pilot’s legs. Moving the cyclic stick in any horizontal direction causes the rotating wings to increase their pitch and move higher on one half of their cycle while feathering on the other half. This cyclic change of pitch causes the disk they form to tilt and move in the same direction as the cyclic stick is pushed.” Now, along with my left hand moving up and down and twisting, my right hand moved in small circles above my knees as, in my mind, I flew.

“The force that rotates the main rotor system clockwise as seen from the cockpit also tries to rotate the fuselage under it in the opposite direction. This effect is known as torque. The way it is controlled is with the an titorque rotor, the tail rotor located at the end of the tail boom. When it is spinning, it pushes the tail sideways against the torque. The amount of push, and therefore the direction the nose points, is controlled by pushing the foot pedals. Pushing the left pedal increases the tail rotor pitch, which pushes the tail to the right, against the torque, moving the nose to the left. The right pedal reduces the pitch and allows the torque to move the nose to the right. Because this left-and-right turning requires more and less power, you will have to adjust the throttle accordingly to maintain the proper engine and rotor rpm. Got that?”

I thought I did. I moved my left hand up and down, twisting it, to control the imaginary collective and throttle; my right hand moved in small circles, pretending to control a cyclic; my feet controlled the tail rotor by pumping back and forth. Eventually I could do all these movements simultaneously. These exercises and the fact that I already had a fixed-wing pilot’s license gave rise to the fantasy that I would be able to fly a helicopter on the first try.

“Okay. See that tree out there?” The orientation instructor’s gravelly voice hissed in my earphones. I was finally getting my chance. The instructor held the H-23 Hiller trainer in a hover in the middle of a ten-acre field.

“Yes, sir,” I said, squeezing the intercom switch on the cyclic stick.

“Well, I’m gonna take care of the rest of the controls, and all I want you to do is to keep this bird pointed in the direction of that tree.” He jutted his chin forward. I nodded. “You got that?”

“Yes, sir.” My senses were overwhelmed by the clamor and bouncing and vibrations of the H-23. The blades whirled crazily overhead; parts studied in ground school in static drawings now spun relentlessly and vibrated, powered by the roaring, growling engine behind my back. All the parts wanted to go their own way, but somehow the instructor was controlling them, averaging their various motions into a position three feet above the grass. We floated above the ground, gently rising and falling on an invisible sea.

“Okay, you’ve got it,” my instructor said. I pushed first one and then the other of the spongy pedals, trying to turn the machine while the instructor controlled the cyclic and collective. All I had to do was point the helicopter at the tree. The tree swung wildly one way and then the other.

“You see the tree I’m talking about?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, try to keep us pointed that way, if you don’t mind.” This instructor, like all the IPs in the primary phase of instruction, was a civilian who’d been in the military. The fact that they were now civilians did not cramp their cynical teaching style.

I concentrated even harder. What could be wrong with me? I already knew how to fly airplanes. I thoroughly understood the theory of controlling helicopters. I knew what the controls did. Why couldn’t I keep that goddamn tree in front of us? Swinging back and forth in narrowing arcs, learning to anticipate the mushy response in the pedals, I finally succeeded in keeping the tree in front of us most of the time, plus or minus twenty degrees anyway.

“Not bad.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Now that you have got the pedals down nice and good like you do, maybe we ought to show you how this collective-pitch stick works.”

“Okay, sir.”

“What I’m going to do is to take all the controls again”—the IP put his feet back on the pedals, and the tree immediately popped to a stable position dead ahead of us—“and then let you try your luck with

the collective: Just the collective. Try to keep us about this high off the ground. Okay?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You got it.” This phrase always preceded the transfer of control.

“I’ve got it.” The moment I grabbed the collective stick in my left hand, the helicopter, the same helicopter that had been sitting placidly at three feet, lurched to five feet. It seemed to push itself up. I pushed down too hard to correct. We strained up against the harnesses as the ship dropped. I panicked and overcontrolled again as the ground rushed up. I pulled up too hard, causing us to pop back up to six or seven feet.

“About three feet would be fine.”

“Yes, sir.” Sweat dripped off me as I fought to achieve a stable altitude above the ground. It wasn’t a matter of just putting the collective in one position and leaving it there; constant corrections had to be made. After a few minutes of yo-yo-ing up and down I was able to keep the machine about where the IP wanted it.

“That’s real good. You’re a natural, kid.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“I’ve got it.” The IP took control of the collective. “One small thing you’re going to have to know is that when you pull up with the collective, that takes more power, which causes more torque, which means you have to push a little left pedal to compensate. You have to push a little right pedal as you reduce the collective.”

“Yes, sir.”

“The next control we’re going to try is this here cyclic stick. You don’t move this one much, see.” I looked at the IP’s right hand as it held the cyclic-control grip. It was moving plenty. The top of the cyclic vibrated in agi. tated harmony with the shaking machine.

“It looks like it’s moving a lot to me, sir.”

“I didn’t say it wasn’t moving; I said you don’t move it much. There’s a difference. The H-23 is famous for the excessive motion of its cyclic. That’s the feedback from all that unbalanced crap spinning around up there. Try it for a while. You got it.”

“I got it.” I put my hand on the wavering cyclic grip between my knees. I could feel strong mechanical tremors vibrating in many directions within my white-knuckled grasp. The IP had the rest of the controls. The H-23 held its position for a few seconds and then began drifting off to the left. I pushed the tugging grip to the right to correct. Nothing seemed to happen. We still drifted left. I moved the grip farther to the right. The ship then stopped its leftward drift, but instead of staying stable, like I thought it would, it leaned over to the right and drifted in that direction. It felt like there was no direct control of the machine. I pulled the cyclic back to the left quickly, to correct, but the machine continued to the right. The helicopter was taking on a personality, a stubborn personality. Whoa, I thought to the machine-turned-beast. Whoa, goddamn it. I increased pressure away from its drifting, and once again it halted, seemingly under control, and then drifted off in another direction.

“I would like it better if you kept the helicopter over one spot or another that we both know about, if you don’t mind.”

“Yes, sir.” After a series of hesitating lurches in many different directions, I finally caught on to the control delay in the cyclic. After five minutes of sweaty concentration I was able to keep it within a ten-foot square.

“Well, you got it now, ace.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Next thing to do, now that you’ve got the cyclic down, is to let you try all the controls at once. Think you’re up to that, kid?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Okay, you got it.”

“I got it.” The cyclic tugged, the collective pushed, and the pedals slapped my feet, but for a brief moment I was in complete control. I was three feet off the ground hovering in a real helicopter. A grin was forming on my sweaty face. Whoops. The illusion of control ended abruptly. As I concentrated on keeping us over one spot with the cyclic, we climbed. When I pushed the collective back down to correct, I noticed we were drifting backward, fast. I corrected by pushing forward. Now I noticed we were facing ninety degrees away from where we started. I corrected with the pedals. Each control fought me independently. I forgot about having to push the left pedal when I raised the collective. I forgot the cyclic-control lag. We whirled and grumbled in a variety of confusing directions, attitues and altitudes all at once. There were absolutely too many things to control. The IP, brave man that he was, let the ship lurch and roar and spin all over that field while I pushed the pedals, pumped the collective, and swept the cyclic around, with little effect. I felt like I had a handful of severed reins and a runaway team of horses heading for a cliff. I could not keep the machine anywhere near where I wanted it.

“I got it.” The IP took over the controls. The engine and rotor rpm went back to the green. We drifted down from fifteen feet to three, pointed away from the sun and back to the tree, and moved back to the spot where we had started. I felt totally defeated.

“Well, it’s true what they say about you all right, ace.”

“What’s that, sir?”

“You’re a natural.”

“A natural? Sir, I was all over the field.”

“Don’t worry about it, kid. We’ll just keep practicing in smaller and smaller fields.”

Our actual flight training with our regular instructors began the following day at a stage field, one of many scattered over the central Texas prairies. The stage fields provided each flight with a private airfield, thereby separating advanced and beginning students. The first challenge was to solo. To this end, the IP concentrated on basic maneuvers like hovering, takeoffs, landings, and simulated forced landings, which are called “autorotations.”

The army taught us to fly the machine as if the engine would quit at any moment. Throughout training, whether you were trying to hover, take off, land, or just cruise, the IP would cut the power, to see how you’d react. When he decided you might survive a real emergency alone, then you would solo.

My IP, Tom Anderson, would wait to cut the power until we were crabbing sideways or bucking in somebody’s rotor wash or ballooning too high in a hover. He wanted to see how we would react when everything else was going wrong. There was no way you could be ready for it. We learned to react automatically when the power quit.

There were two ways to autorotate. In a hover, you held the collective where it was when the power was cut until the skids were six inches from the ground; then you pulled it up to cushion the landing. In flight, you immediately pushed the collective fully down to neutralize the pitch angle. With the pitch flat, the rotors would continue spinning, providing lift, as the helicopter descended. If you held the collective in flying position, the rotor blades would slow and stop. Because the rotor blades were rigid only by virtue of the centrifugal force of their spinning, the stopped blades would simply fold up and the helicopter would fall like a streamlined anvil. It was fatal not to push the collective down. Autorotations were quick. A Hiller in autorotation descends at 1700 feet per minute. From 500 feet we had twenty seconds to react to the power failure, bottom the pitch, find a spot, and land. In this short glide you maneuvered the machine to any clearing in range. At roughly fifty feet from the ground you pulled the cyclic back, making the ship flare, trying to slow it from 45 knots to zero. With the nose high in the flare, you waited until the tail rotor was close to the ground, pulled a little pitch, and leveled the ship. You saved the rest of the pitch to cushion the landing. That was how it was supposed to go.

At first I hit the ground too hard, or pulled the pitch too soon, or landed crooked. After bouncing around awhile, practicing hovering autorotations in the parking area and down the lane at the stage field, we’d get to the takeoff mark at the end of one of six lanes. There I would attempt to hover the machine, talk to the tower, and be ready for a hovering autorotation at any moment.

“Zero-seven-nine lane three for takeoff.” After saying this, I would turn ninety degrees, wait for clearance, and make the takeoff.

For takeoff from a hover, you pu

shed the cyclic slightly forward and added a little power by pulling up on the collective, twisting the throttle appropriately to maintain rpm. The helicopter would accelerate across the ground, pretty much at hover altitude, until it reached the point of translational lift. Translational lift was that speed—in the H-23 trainer it was about 20 miles an hour—at which the rotor system moved into undisturbed air and suddenly became more efficient. At that point you could feel it jump into the climb. (That is how overloaded helicopters, unable to hover, can still fly if they make running takeoffs.) From translational lift you attempted to hold a constant airspeed and climb rate until you reached the altitude where you turned to follow the traffic pattern. Because there were six lanes at the stage fields, staying accurately in the traffic pattern was crucial. Midair collisions were not uncommon between students.

Once airborne, we were subject to autorotations on each leg of the rectangular pattern. After we took a few turns around the pattern, practicing landings and takeoffs, the IPs usually took us out to the surrounding countryside and had us work on cruising flight and autorotations.

We spent an hour each day in the cockpit and three or four hours in the bleachers watching our classmates. We read the flight-school syllabus of maneuvers. We attended ground-school classes in aerodynamics, weather, and maintenance. We lived and breathed flying. We waited expectantly for the first of our classmates to solo.

After two weeks, one did. We threw him into a pond, the traditional honor after the first solo. He could also wear his hat forward. By the end of the third week, nearly half the class had been thrown into the pond and were wearing their hats forward, and I was one of them. At the end of the fourth week, those who hadn’t been able to solo were eliminated from flight training.

The next challenge was to learn all the primary maneuvers well enough to pass a check ride in four more weeks. We flew more often. Each day, I. flew an hour of dual with Anderson. Additionally, he assigned us another hour-and-a-half solo in which to eliminate whatever errors he had pointed out. When next we flew dual, we would be expected to demonstrate improvement. Pleasing the IP meant becoming a pilot and a warrant officer instead of a pfc infantryman. Getting the maneuvers right in the air, and worrying about them on the ground, became a total occupation.

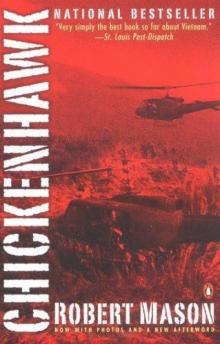

Chickenhawk

Chickenhawk