- Home

- Robert Mason

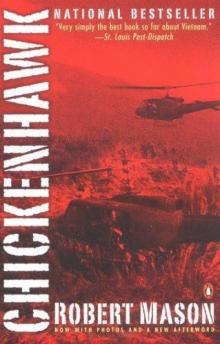

Chickenhawk Page 15

Chickenhawk Read online

Page 15

“It’s pretty on this side of the pass,” said Riker.

It was pretty. The tall grass flowed over the hills. The soil was red where ravines and road cuts exposed it. With the exception of the two American compounds and the village of Pleiku ahead, it looked uninhabited from the air.

We were close to the adviser compound. “Where we’re headed is about five miles due south of that little airstrip at Holloway,” I said.

“Where’s the company going to set up camp?” asked Riker as he looked out his triangular window.

I checked the map. “See that big field there, between Holloway and New Pleiku?”

“That’s it?”

“Yep. It’s been named the Turkey Farm.”

Riker and I landed at the edge of a sea of tents: the grunts’ camp, called the Tea Plantation, adjacent to a real one owned by a Frenchman.

The man we were assigned to support, Grunt Six, was a full colonel, or “bird colonel,” as they say. He ran toward us in a crouch, ducking the rotors. Two captains followed, one wearing pilot’s wings. They climbed on board and grabbed the radios their assistants handed them. While they set up the radios, the captain with wings leaned forward between our two seats and pointed to a spot on a map where he wanted us to go and motioned thumbs-up for takeoff.

Riker brought the Huey up to a hover and nosed it over to go. As we climbed to the altitude they wanted, I turned around to watch.

Grunt Six and the other captain sat on the bench seat facing forward. Coiled cords ran from their headsets to the pile of radio gear on the deck in front of them. The other captain, assigned to aviation-liaison duty with Grunt Six, sat forward on the floor with his back to us. He was supposed to advise the grunts on how to use the aircraft and the crews assigned to them.

The infantry commander and his assistant studied a plastic-covered map mounted on a square board balanced on the assistant’s knees. They talked through their own intercom system, and the assistant made marks on the map with a grease pencil.

Grunt Six switched his radios constantly from one channel to another. I tried to listen in, but I didn’t know which frequencies he used. Once in a while, he would come up on the channel I monitored.

“Red Dog One, Grunt Six.” The number six in the call sign always meant boss, chief shit. Red Dog One was the radio call sign for one of his subordinates, probably a lieutenant, leading a patrol in the woods below.

“Yes, sir.”

“Status.”

“No contact yet. Still proceeding on azimuth one-eight-zero.”

“Roger, maintain, out.” He immediately switched channels to someone else. He was all business. There were thousands of men down there among the bushes and tree clumps, over their heads in elephant grass, trying real hard to make contact with the retreating NVA.

If I hadn’t loved flying so much, the job would have been boring. All we had to do was fly compass courses that crisscrossed the south end of the valley. The aviation captain hooked into our intercom and gave us the new headings as Grunt Six dictated.

At the far south end of the valley, about eight miles north of the Chu Pong massif, Grunt Six had established a forward command post on the top of an isolated hill. At about two o‘clock the captain gave us the coordinates and told us to take them there. The valley from the hill to the massif was all flat plains covered with elephant grass. It ended where the Ia Drang River changed course and the ground rose sharply to a massive plateau of rough, tree-covered mountains that descended gently on the other side into Cambodia. At the base of the rise was the beginning of a series of sharp, jungle-covered foothills that twisted their way up into the massif. It was in these foothills that the enemy was thought to have a base.

Riker flew to the lone hill covered with tall brown grass and a few small trees. Circling once to see where they wanted us to land, he made the approach. As we came in over the edge of a sharp drop-off covered with tall bushes, a pup tent flew away in our rotor wash. Its owner bounded off through the tall grass trying to catch it. We landed about a hundred feet from the headquarters tent, sinking into the grass up to the cargo deck. The captain with wings jumped out and signed a cut-throat and Riker shut down the Huey.

Grunt Six marched off to the tent. His other assistant said, “We’ll be here an hour, so get something to eat.”

So far, so good. This command-ship flying was okay. At least we weren’t in the assaults going on near Pleime.

While the rotor was spinning down, Reacher pulled the C-ration case from the aft compartment. I walked past the still-spinning tail rotor to see how the kid who lost his tent was doing. He was peeling his tent from a bush below the steep edge of the hill, up to his armpits in weeds. The tent was snagged on something, but he finally got it loose. Clutching it to his chest, he trudged back toward me.

“Sorry about that,” I said. “We didn’t see you when we came in.”

“Oh, that’s okay, sir.” He smiled and threw the tent down near a bush. “I didn’t want you to see me. I’m building a camouflage position here.” He pointed proudly to a pile of brush near his crumpled tent.

“Well, that could be a bad spot for it.” I nodded back toward the Huey. “You’re downwind, and you’ll be on our approach path every time we land.”

“I never thought of that.” He wiped his forehead with his T-shirt, pulling the stretched-out bottom up to his head. “How come you don’t come in like this?” He made his hand stop in midair and drop straight down.

“Vertically,” I said.

“Vertically. Can’t a helicopter do that?”

“We can in a pinch,” I said, “but it’s dangerous. We like to keep some forward motion so we’ll be able to autorotate in case we lose power. What we can do, now that we know where you are, is to come in a little steeper, which should keep you out of the rotor wash. But another helicopter coming in here will just blow everything away again.”

“Well, thanks for explaining that. But I think I’m just going to rebuild it here, stronger.” He smiled and started back to work.

“You want beef with noodles or boned chicken?” Riker came up beside me.

“Neither.”

“That’s all we got.”

“Boned chicken.” Riker threw me the box and walked back to sit on the edge of the cargo deck.

Riker and I and Reacher and the gunner sat around the Huey and ate lunch. Grunt Six was in the headquarters tent, making plans.

I approached the headquarters tent after lunch. About five of the fifteen or so grunts on the hilltop were outside the tent hanging around. I said hello and sat down on a stack of C-ration cases. Beyond the group of T-shirted enlisted men, I could see the wooden legs of a map tripod through the tent door. The meeting between Grunt Six and his men was still going on.

A Vietnamese soldier walked out from the tent. He was dressed in the camouflaged, tight-fitting, big-pocketed uniforms of the Vietnamese Rangers. He was, however, not a ranger but an interpreter. He was smiling. A smile is a safe thing to hide behind. I waved him toward me, happy to see an interpreter. I saw this as a chance to learn how the people here really felt about the war. The Cav was so isolated from the ARVNs, I had never had a chance before.

“Hello,” I said.

“Hello,” he said.

“I’ve been wanting to talk to a Vietnamese who spoke English.”

“Yes,” he said knowingly.

“Well, how do you think we’re doing so far?”

“Yes,” he nodded.

“No, I meant how do you think we’re doing? Are we winning?”

“Yes, that could be so,” he assured me. “How are you?”

“Me?” Must have trouble with my accent. “I’m fine. Fine.”

“I am fine, thank you.” He bowed slightly.

I looked quickly over to the smiling faces of the grunts and realized that they all knew he couldn’t speak English worth a shit.

“Great,” I said. “I understand that this hill is going to sink into the val

ley today.”

“Yes, that could be so.”

What fun. “They’ve been thinking about moving Saigon up here this weekend so we won’t have so far to go for R&R.” I heard a little cheer from the watchers.

“Saigon.” He nodded with happy recognition.

I was just getting into it when a private stepped out of the tent and yelled, “Hey, Nguyen.” The smiling, wide-eyed interpreter nodded abruptly and ran back to the tent. At least he knew his name.

At about three o‘clock we loaded up and flew back to the Tea Plantation. Grunt Six had us drop him off near a waiting Jeep. We hovered over to a fuel bladder at one end of the field to refuel. We returned to the hilltop command post by ourselves. I made the landing steeper, and this time the brush blew away, but the tent stood.

At the HQ tent the officer in charge, a captain, showed us what they were up to on the big map on the easel. The gist of the business for the rest of the afternoon was to move men around. They were ganging up the patrols where they had had some action.

We flew all over the south end of the valley all afternoon without incident. Sometimes a single ship was safer than a group. Our explanation for this phenomenon was that the enemy thought a single ship was scouting for them, so they didn’t fire and give away their position. Later we found out we had been flying over Charlie all day.

By late afternoon we were looking forward to rejoining our company. They’d be at the Turkey Farm by now, eating inside the adviser compound. In a real mess hall. Taking real showers. At this point we had logged six hours, and Riker and I were both pretty tired.

“Tonight we want you to fly the old man again,” the captain at the command post told us after we landed. “You’ll be flying this end of the valley so he can talk to his people here.” He pointed to the map. “Shouldn’t take more than a couple of hours. When you finish, though, we want you to stay at the Tea Plantation. The Colonel isn’t finished with you yet.”

The couple of hours became more than four, and we finished at ten o‘clock. Grunt Six sped away in his Jeep among the thousand tents that crowded the field. We were left to fend for ourselves. Len had mentioned that our company and our gear were only five miles away, but Grunt Six wanted us to stay here.

“Park your chopper down by that Medevac,” he said to Len before he left. His deep voice matched his thick build. “Go find those boys from that helicopter and tell them to give you a place to sleep. Gotta have you boys around here in case I need you quick.”

The “fatigue factor” in flying helicopters for long periods is high. The constant vibrations, deafening noise, and total concentration required made the army restrict pilots to four hours of flight time per day. Four hours was a good workout, and still twice as much time as some of our jet-jockey cousins in the air force flew. Naturally, the realities of combat pushed us beyond these limits nearly every day. Six or eight hours was pretty common in the Cav. Len and I had just flown ten hours for Grunt Six, and as we watched him disappear into the darkness, we felt numb. We were both so tired that we didn’t want to mess with the C rations. Instead we wanted to find that other helicopter crew and get a place to sleep.

We found them about two hundred feet from their Huey in a four-man tent. “I don’t know why he told you to find us. There’s no extra tents here,” a tall warrant officer told us. “You’re welcome to sleep on a couple of our stretchers if you want. They’ll keep you off the ground.”

“That would be good,” said Len. “Our crew chief and gunner can have the Huey to themselves.” He nodded toward our distant ship, invisible in the darkness. “No fun trying to sleep all four of us in there.”

“Well, you’re welcome to set up right here.” He pointed to the ground in front of their tent with a flashlight. “We even have a poncho you could string up for shelter.”

“Naw, that’s okay,” said Len. “Looks like it’ll be clear tonight. Won’t have to fuck with it.” I looked up at the starry sky. It was inky black, with bright jewels of stars. The stars looked almost the same here as they did on the other side of the world. Polaris was closer to the horizon. Big Dipper there. Orion. I had spent a lot of time looking at the stars as a kid. I kept hoping that I’d be able to see the Southern Cross.

Len had been calling my name several times. “Bob, you okay?”

“Yeah, just looking for constellations.”

“Well, I don’t know about you, but I’m tired enough to sleep standing up. I’m going over to get one of those stretchers.”

“Me, too.”

I went first to our ship to make sure Reacher and the gunner knew where we would be. I picked up a stretcher from the Dust Off ship. “Dust Off” was the radio call sign for the Medevac helicopter. I was developing the habit of calling everything by its call sign. I put the stretcher under my arm and walked off toward the Big Dipper, in the direction of the tent. With the activity of our setting up the stretchers, the Dust Off pilots stayed up to talk awhile.

I was pretty quiet. While Len and the tall warrant officer talked about their recent adventures, I sat on the stretcher looking interested, somehow believing that they could see my face when I couldn’t see theirs. I sat that way for a minute and then decided to lie back and look at the stars.

The back of my hand touched something cold and sticky beneath my head. I sat up quickly and said, “What’s that?”

The other pilot from the Dust Off crew pointed a flashlight at the stretcher. A small piece of human flesh was spotlighted on the green canvas. “You gotta brush them off pretty good,” he said. “Stuff sticks like crazy.” He shrugged with professional aplomb and reached over to push it off with the flashlight. The red part stuck tightly. He finally peeled it off with his fingers and tossed the unidentifiable piece of person into a clump of grass.

I was pretty awake now, so I listened.

“One of our ships went into a hot LZ and picked up four wounded,” the warrant said. “They were doing okay until they took off. Flew right over the machine guns. Charlie shot the living shit out of them. Killed the whole crew and all the wounded when it crashed.”

His buddy with the flashlight continued. “And we got shot down during Pleime,” he said as he wiped his hand on his trousers. “We landed too close to some trenches the gooks had dug right next to the Pleime compound. The guys inside didn’t know that Charlie was that close. Anyway, we went in to pick up some wounded. They got us on our approach. Killed the gunner. We had to jump out and run for it. We just made it into the compound.” He paused while his partner grunted in agreement. “That’s why we can’t land in hot LZs anymore. Charlie thinks the red cross on the side is a bull‘s-eye. Fuckers don’t respect the Geneva accords at all.”

“Geneva accords?” I said.

“Sure, the agreement is that ambulances, even air ambulances, are supposed to be left alone,” said the shorter warrant.

“I,don’t think Charlie ever signed the Geneva accords. I know the United States didn‘t,” I said. I was becoming argumentative, against my will. “The accords don’t allow shotguns, either, but I know we have crates of them at our company for perimeter defense.” I put this fact on the scales to balance Charlie’s transgressions against Dust Off. I had always enjoyed playing devil’s advocate, and here I was, behaving true to form, defending our enemy.

“Whose side are you on?” the tall warrant asked.

“It may sound bad,” I said, “but if neither side signed the agreement, then one side can hardly accuse the other of breaking the agreement.”

“You can if the other side is a bunch of fucking gooks,” the tall warrant said angrily.

The opposition made an interesting point. He also outweighed me by forty pounds. “Well,” I said, “that’s another way of looking at it.”

“I think rules for war is a crock of shit,” said Riker. I couldn’t see his face, but I knew he was smiling.

“I agree,” the tall warrant said. “I think that war is war, and we should get this one over with and go h

ome.”

“We might do that soon,” said Riker. “If we can trap the NVA before they get to Cambodia, we’ll knock the shit out of ‘em.” Riker paused, and our hosts grunted their agreement. “After we knock the shit out of ’em, I think they’ll want to quit fighting and make peace. They’ll want to give up and go home.”

“I’m for that,” I said.

It was eleven-thirty. Everyone was tired, and we decided that we would put off winning the war until tomorrow morning. I switched ends on the stretcher to avoid the stain from the piece of meat.

Lying on my back, I watched the stars again. Stuff watching stars. My thoughts drifted to the other side of the world, where Patience, at this same moment, would be getting Jack to the table for lunch. When I last saw him, he was fourteen months old and just beginning to toddle around without falling down too much. He liked to play a game of not doing what his mother wanted him to do.

“Time to eat, Jack,” she would say. “No.” He would laugh and run to the bedroom. “Jack, come to the table.” Jack giggled in the bedroom, climbing up on our high bed. Patience came to the doorway and looked in, smiling. “Jack, you come eat right now. It’s not time to sleep.”

“No.” He laughed defiantly.

“Yes. Now, get up,” she said firmly.

“Come on, get up.” Riker shook my shoulder.

“What?” I opened my eyes, and the stars were still there. “What time is it?” Maybe if I pointed out what time it was, he would change his mind.

“Twelve. We’ve got to go on another mission, right now.”

“Mission?”

“Yeah. Come on. Grunt Six is going to meet us at the chopper in ten minutes.”

We got to the ship and woke up Reacher and the gunner. Minutes later, I could see the tent shadows cast by Jeep headlights dancing across the side of the Huey. The Jeep stopped fifty feet away. Figures walked from behind the headlights into their bright cones of light. Silhouette tunnels of darkness arrowed out and wavered in front of them.

Grunt Six approached Riker and me with his two captains in tow.

Chickenhawk

Chickenhawk